The Hubble Space Telescope (HST) is a high end telescope that was launched to earth’s orbit at an altitude of approximately 540km in the year 1990 and has been in operation since. Besides the fact that it is an amazing engineering feat, the HST is infamous for the optical malfunction that was discovered within a few weeks after its launch.

The Hubble Space Telescope is a classic System Engineering case which is raised as an example or fully analyzed at one point or another of any System Engineering course or seminar. I personally co-presented it with 2 other colleagues as a case-study in one of such courses, without the optics simulations of course.

It so happens that the HST is a classic case for this blog’s purposes – it is an optical malfunction case that may be explained with pure optics, which had to be solved by the whole engineering team led by the System Engineering team.

As such, the Hubble Space Telescope will be described in detail from the Optical Engineering point of view in this first post out of 3 posts series and in the next posts we will discuss what went wrong, why it went wrong, what was the effect of it and how it was fixed.

In this post series I used published information from the following sources:

- Wikipedia

- NASA Optical Systems Failure Report

- NewScientist

- Vision Systems

- The Hubble Space Telescope Servicing Mission

Please note that I deliberately neglected certain details in some parts of the story and went into greater details in other parts, that is to have a whole story from beginning to end but without giving a 100+ pages report. For the full story and fine details you may start from the official NASA report and work your way up from there.

All the optical simulations in this post series were done using Quadoa optical design SW. Note that because I did have access only to some reports by NASA (obviously) the optical simulations were done to the best of my understanding with the available information and may not be accurate to the last decimal point. I tried to have it as close as possible of course so that the phenomena and the conclusions are aligned with reality.

Telescope Review

The Hubble Space Telescope is a Ritchey-Chrétien telescope. But what is a telescope? Well, a telescope is an optical system that allows us to see very far. I hope that was not news for the reader. ![]()

A little history: sometime in the 1600’s Hans Lippershey invented the first telescope shortly after to be improved significantly by Galileo Galilei to discover Venus (and earth) orbit the sun among many other astronomical discoveries. In 1611 Johannes Kepler invented the Keplerian telescope (Duh!!! ![]() ) which led him to formulate the Kepler laws of planetary motion. In 1668 Issac Newton invented the reflector telescope to avoid the chromatic aberrations which were an inherent issue in the refractive telescopes, which in turn paved the way for Laurent Cassegrain, William Herschel and of course George Ritchey and Henri Chrétien to come up with their designs for reflective telescopes. All these designs differ in their light collection methods and capabilities, NA (or f/#), magnification and so on. Telescopes is a field in optics where we may easily see quite a few viable competing solutions for the same problem.

) which led him to formulate the Kepler laws of planetary motion. In 1668 Issac Newton invented the reflector telescope to avoid the chromatic aberrations which were an inherent issue in the refractive telescopes, which in turn paved the way for Laurent Cassegrain, William Herschel and of course George Ritchey and Henri Chrétien to come up with their designs for reflective telescopes. All these designs differ in their light collection methods and capabilities, NA (or f/#), magnification and so on. Telescopes is a field in optics where we may easily see quite a few viable competing solutions for the same problem.

Note that all of the large size and nearly all medium size telescopes operating nowadays are reflective telescopes with the notable advantage of reflective designs in their indifference to wavelength. Unlike refractive optics (lenses) where each wavelength experiences a different refractive index which results in chromatic aberrations, mirrors reflect all wavelengths into the same optical path. These reflective designs allow the use for a very wide range of wavelengths using different sensing devices and cameras with the same mirror\s to form the image.

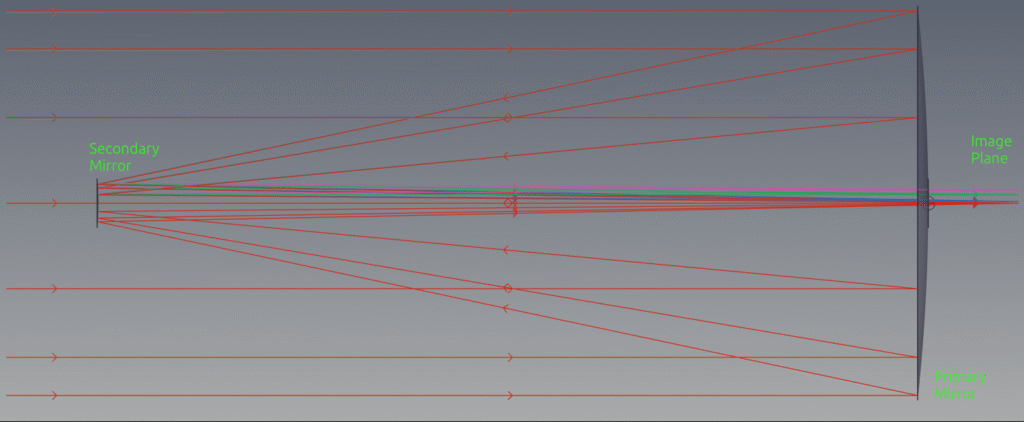

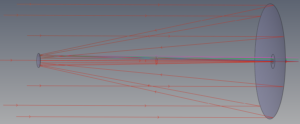

Ritchey–Chrétien Telescope

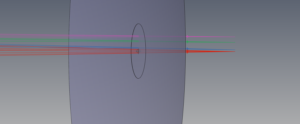

The Ritchey–Chrétien architecture is based on 2 mirrors – the primary (big) mirror collects and diverts the rays onto the secondary (small) mirror which in turn focuses the rays onto the image plane. The primary mirror diameter is 2.4m and the secondary mirror diameter is 0.3m. Take a look at the simulated design below:

This architecture has the inherent advantage of being able to collect large amount of rays to be able to detect very faint light emitting objects.

The HST was designed to operate in the wavelength range of 110-1100nm. The advertised resolution of the Hubble space telescope was 0.05-0.1 arcsec in the visible range. This number is essentially diffraction limited if we recall the angular diffraction limit formula for the Reighley criterion:

So in our case the diffraction limit for 500nm wavelength is 0.279E-6 Rad or 0.160E-4o (or 0.057 arcsec). Anything we simulate below that number is already diffraction limited.

BTW, nowadays earth telescopes’ typical angular resolution goes down to around 0.5 arcsec in average and in excellent (and rare) conditions even to 0.3 arcsec and slightly lower with Adaptive Optics, so the HST was meant to be better than today’s ground telescopes. Just for reference, the HST’s younger “brother”, the James Web Space Telescope, is designed to a resolution 0.032 arcsec in the near-IR range i.e. better resolution for even longer wavelengths.

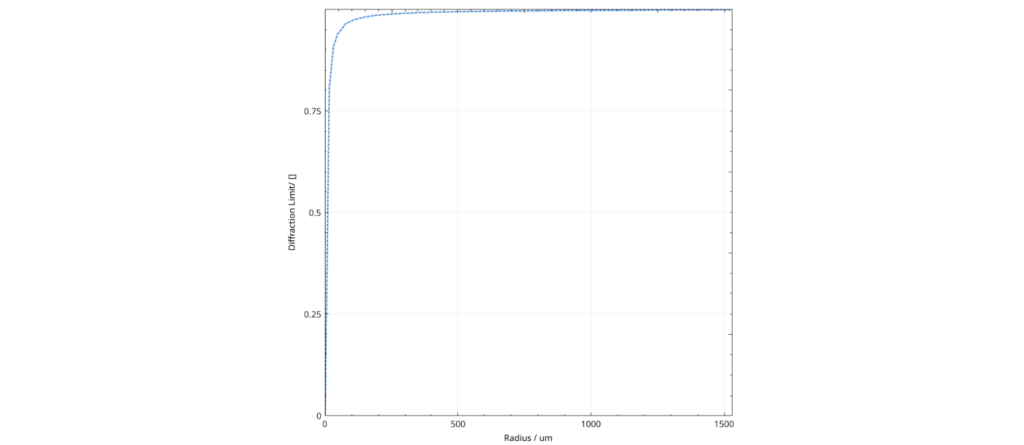

Let’s look at our simulation to verify it caught the system resolution correctly:

This graph represents the enclosed energy of the system. It has two lines – a dashed black line that represents the diffraction limit of the optical system and a solid blue line of the simulated performance of the lens. I used this method of resolution representation to align with NASA’s Optical Systems Failure Report representation (figure 5-1 if one of you readers want to review the report).

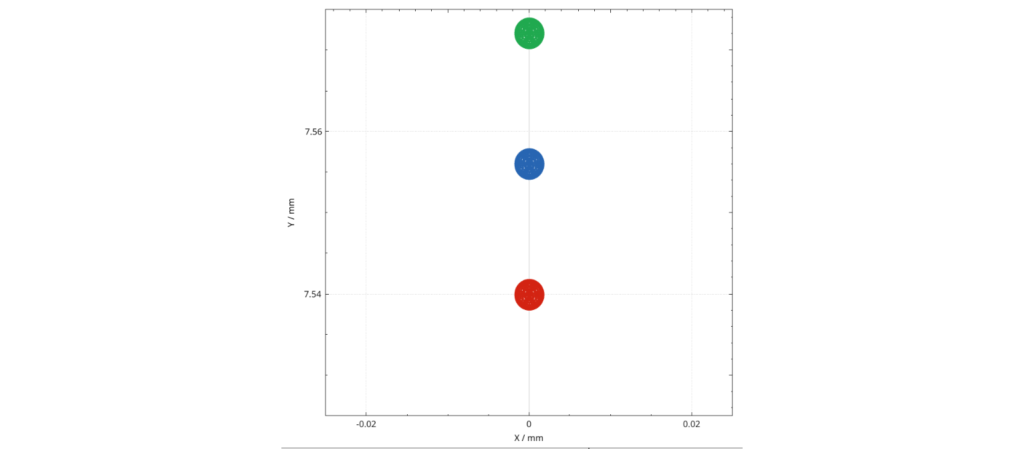

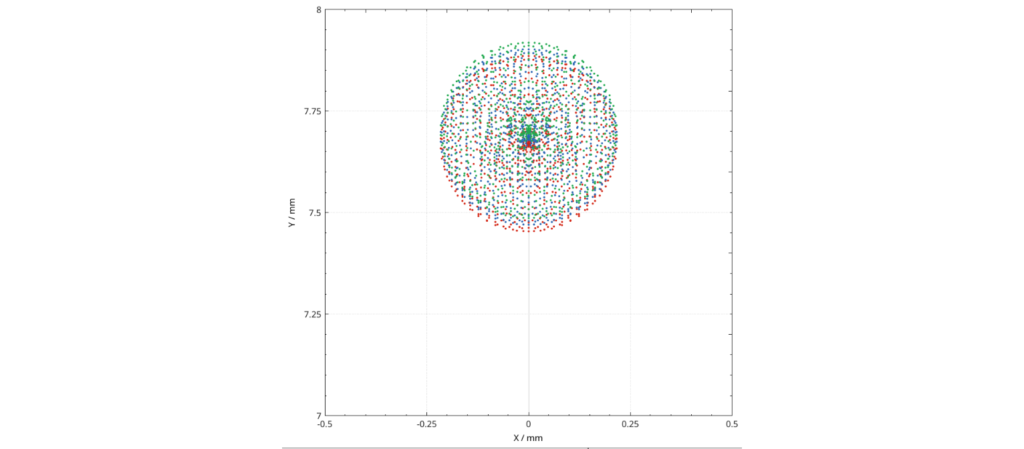

In a more intuitive method, take a look at the following simulation of the spot diagram of 3 fields, separated by a 0.05 arcsec between them.

Our simulation got it right as we may see – the spots are completely separated so the limitation of the design is the diffraction and the enclosed energy graph shows diffraction limit compliance. Note I ignore the camera pixel size for these cases – let’s assume that the camera pixels were adequate for the required resolution.

Engineering Advantages of the HST

A question that must be asked of course, why should we send a telescope to outer space?

The main advantages of having a telescope in outer space are as follows:

- No interference or absorbance from earth’s atmosphere which enable higher optical resolution and lower light requirements

- Space telescope does not suffer from light pollution

- A space telescope is not limited by weather

- Ground telescope is limited to the timings and field-of-view (FOV) in the sky when the targets are above the horizon. A space telescope has a larger sky FOV and much more continuous hours which enables longer tracking of objects in space

- Because space is very cold, a space telescope enjoys higher signal-to-noise-ratio (SNR) for infrared wavelengths which is difficult to achieve on the ground because of earth’s temperature

The Hubble Telescope Is Just A Medium To Big Sized Telescope – In Space

As mentioned before, the HST is a Ritchey–Chrétien telescope and not a really big one with a primary mirror of 2.4m in diameter. There are Ritchey–Chrétien telescopes on earth with much larger primary mirrors such as the Keck telescopes (10m diameter) or the Subaru telescope (8.2m diameter) in Hawaii, the VLT telescope (8.2m diameter) in Chile and more.

These very large mirror telescopes have the ability to collect more light and deal with fainter signals, a need that is eliminated in the HST due to the fact that the signals do not have to pass through earth’s atmosphere.

Now there is a crucial question that must pop into any US taxpayer’s mind: were these advantages worth of the trouble, the cost, the complexity of sending the telescope into orbit?

The answer apparently is a very big YES, if we take into consideration that a second space telescope, the James Web Space Telescope was successfully launched into space in 2021. The scientific advancements and discoveries that were enabled by the HST are priceless.

The HST Launch – Version 1.0

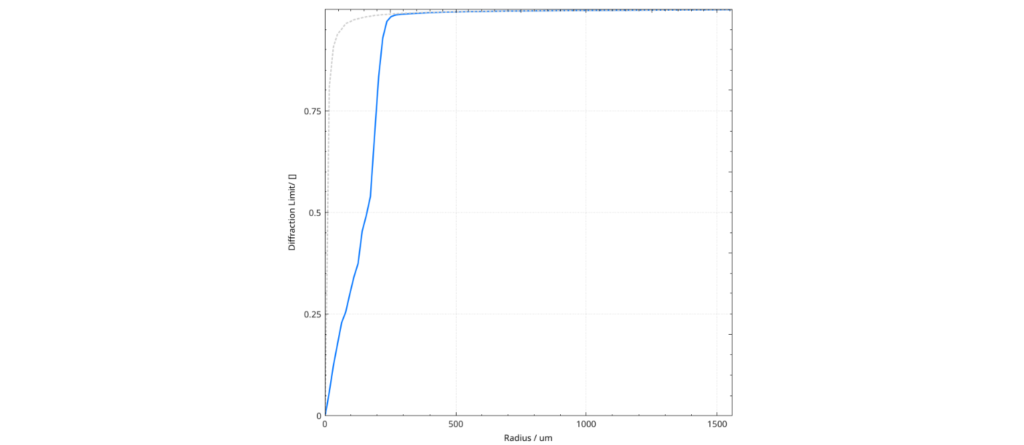

On April 24th 1990 the HST was launched to space on board the shuttle Discovery. Images started streaming in and behold – this is the resolution image the guys on the ground received from the telescope.

When calculated closely the resolution achieved by the HST was closer to 0.7arcesec instead of the required 0.05 arcsec, which obviously is not what the NASA engineers planned to get.

Don’t get me wrong, this is a very good resolution but remember what we always emphasize in system engineering – in-spec or out-of-spec? Pass ATP or fail? In this Hubble Space Telescope, that resolution performance was out of spec.

This is a good place to stop. We have learned what a Ritchey–Chrétien architecture is and how originally it was implemented in the Hubble Space Telescope, what are its advantages and why would we want to send such telescope into outer space.

In the next post we will discover what exactly went wrong with the HST.