On April 24th 1990 the Hubble Space Telescope (HST) was sent to space and soon enough the team on the ground found that the effective resolution of the telescope images is significantly lower then planned. In this post we explore what went wrong and why it happened and most importantly what are the lessons learned from this case.

This is the second post in the HST post series. I strongly suggest that you read the first post in this series since this post is based on it.

First, I would like to emphasize the gravity of the situation: after a long R&D, manufacturing and QA process a state-of-the-art machinery is sent on a space shuttle and successfully enters orbit, only to get images comparable (at best) in resolution with earth-based telescopes. Now, go figure how to troubleshoot engineering issues in outer space.

Resolution Issues

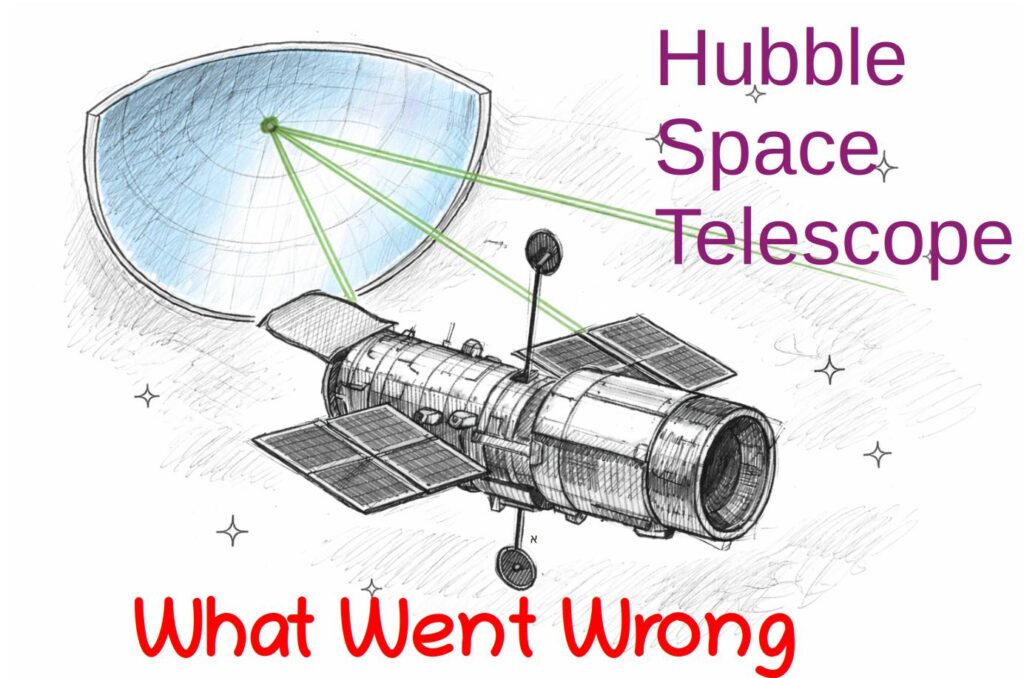

Let’s dwell into the optics of the problem. As a reminder from the previous post, the resolution requirements of the HST were diffraction limited i.e. resolution of 0.05 arcsec in 500nm over a 2.4m primary mirror Ritchey–Chrétien architecture telescope with an f#/24.

In practice the images coming in exhibited a resolution of 0.7 arcsec. See below the graph of the enclosed energy vs. the diffraction limit in a Quadoa simulation of the initial telescope that was sent into orbit in 1990.

Remember, we expected the blue solid line and the dashes line to overlap. That is clearly not the case.

Let’s dig into the optical phenomenon of the issue. The HST exhibited blurred images with spherical aberration in all the cameras and optical paths, indicating that the problem is originated in one or both of the telescope mirrors.

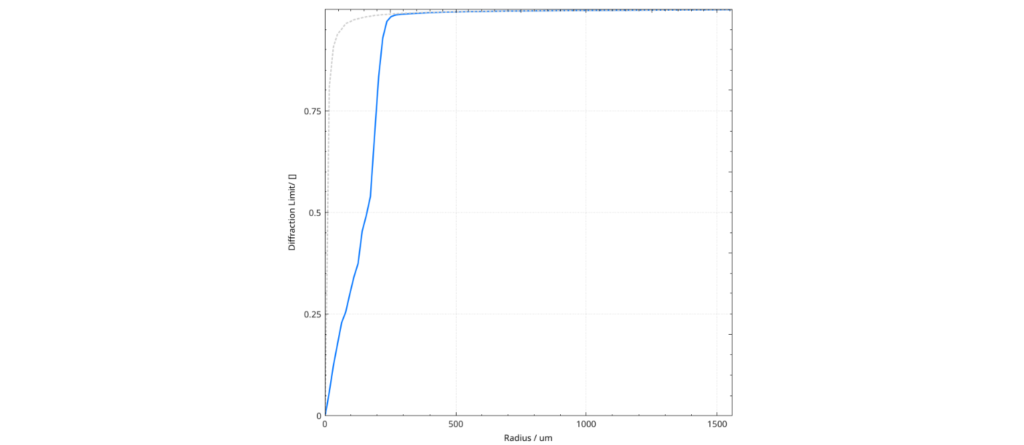

In practice the primary mirror’s conic constant was manufactured in k=-1.0132 instead of -1.0023. The conic constant of spherical surface is a geometric parameter that controls how quickly the surface deviates from a sphere as you move away from the optical axis. Negative k values create surfaces that are “less curved” at the edges (oblate, parabolic, hyperbolic), while positive k creates surfaces that are “more curved”. This is crucial for correcting spherical aberration in optical systems – or in the case of the HST “creating” spherical aberration.

Please see below the different “smileys” presenting the available conic constant values as summarized with the assistance of Claude.ai:

So the primary mirror of the HST was sent to orbit with a slightly steeper parabolic sphere than intended. The effect of such sphere over our image is “simply” a spherical aberration.

Reflective Null Corrector – Optical Testing Method of Large Aspherical Surfaces

We cannot explain what went wrong with the primary mirror’s production without first explaining the method of verification used in the telescope industry for testing large spherical surfaces.

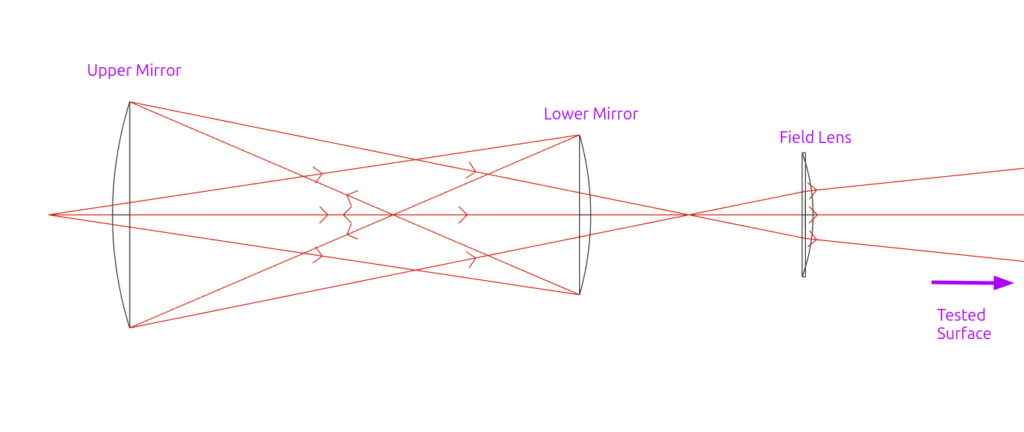

A null corrector is an interferometric device that introduces a wavefront that exactly cancels the aberrations of the aspheric surface tested. When aligned correctly, the interferometer will show an image of null condition i.e. evenly spaced fringes. A reflective null corrector (RNC) uses two mirrors instead of refractive optics to avoid chromatic dependence of the device.

In other words, the RNC will show the desired resulting image if and only if the surface tested is indeed in the desired dimensions and specifications. See below the sketch of our simulation:

There is a crucial caveat in calibration and testing jigs: when aligned correctly. The correctness of our test is as the tolerances and correctness of our jig’s alignment and placement of the object inside that jig.

The Mechanical Error

The HST primary mirror was manufactured by Perkin-Elmer. Its primary test was using a Reflective Null Corrector as explained above.

As it so happens a 1.5m diameter prototype for the HST mirror was successfully fabricated and tested by Perkin-Elmer company to demonstrate their capabilities.

When scaling up the RNC assembly to support the 2.4m mirror there was a measurement rod as part of the assembly tooling. That rod had some kind of an alignment cap for centering that was accidentally measured by the technician working on it as an inherent part of the measurement tool. We will not go into the little details of the mechanical rod lengths and their placement. Let’s just say that it created a 1.3mm difference between the field lens’ actual location and its designed location.

In addition, when scaling up the RNC the design did not allow re-verification of this distance which caused a one-time alignment without the opportunity to verify afterwards the alignment assembly correctness with external tooling.

So, the alignment tool had a 1.3mm shift in the field lens location.

When quickly simulated this shift in our simulation and optimize the curvature and the conic of the primary mirror such that the spherical aberration is minimized we get our system to converge around conic factor of -1.013236 (give or take a few decimal points accuracy issues ![]() , even this simulation is not perfect). I did not attach a sketch or a visual representation of this conic factor error because it is practically invisible to the human eye.

, even this simulation is not perfect). I did not attach a sketch or a visual representation of this conic factor error because it is practically invisible to the human eye.

So there we have it. The primary mirror was not manufactured to spec.

The System Engineering Side of the Error

The most interesting question in this case was how come this manufacturing error was not detected before launching the telescope into space. In the previous section we have covered one testing method that was malfunction. Weren’t there other tests?

Well, as a matter of fact, there were! Before launch there were no less than 6 different tests for this mirror. 2 were done with the misconfigured RNC which obviously showed that the mirror had the correct form and 1 test (focus in Sub-aperture) was not sensitive enough to detect the problem. However, 3 additional tests were performed by Perkin-Elmer (Refractive Null Corrector (RvNC), Inverse Null Corrector and an RNC vs RvNC Transfer Verification) that showed an error or some kind of a discrepancy. Because the RNC was considered the state-of-the-art test for the mirror these errors were wrongly dismissed and the project continued as planned with the Perkin-Elmer mirror.

A full aperture end-to-end test was not performed due to its high costs and could not be justified since all sub-components met their individual specifications. Furthermore, a backup mirror (in the correct shape) has been already manufactured by Eastman-Kodak but this mirror was not used for cross-check or for comparison.

Sometime the testing is neglected or rushed because the testing arrives at the end of the development and manufacturing processes and it suffers from all the accumulated delays of all the previous stages however, the HST primary mirror was manufactured by Perkin-Elmer between 1978 and 1981 when the polishing was concluded. The final post-coating test of the primary mirror was made in 1982, 8 years before the actual launch – there was a delay because of budget issues and the shuttle fleet grounding due to the Challenger Disaster in 1986. Seemingly, timeline shouldn’t have been an issue in this case however, all reports stated clearly that time was pressing and there was a clear political demand to deliver a system in order to keep the project alive and kicking.

Lessons Learned (Relevant Not only to NASA Projects)

Even though most of us do not handle projects in the scale of NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope there is a lot to learn from this case, engineering procedure wise. See below the list of the lessons learned from this case, with my touch to lower down the conclusions to us mortals who are not employed by any space agency. There is not order to this list:

- Identify and mitigate risks

We’ve already discussed risks in the past. The NASA report gave emphasis to the following points:- Identify single point of failure. Single points of failure require special attention during the project.

- Apply precedent failures or previous use cases to the risk factors of the project. In the case of the HST addressing the high probability of having spherical aberration in Ritchey–Chrétien would have gotten the attention of everyone to the discrepancy in the test results.

- Do not skip formal risk analysis, especially in high complexity project.

- Any inconsistency in critical elements must be fully explained. Being the one that insists that everything has to be fully explained sometimes feels like Don Quixote but that is the way to avoid “failures after launch” 🙂 I had to use that pun.

- If I may add to the previous point, when we have a sub-module or a system of which service is difficult or unavailable it is wise to address all the aspects of its failure regularly over the project and give way to all available thoughts and opinions.

- Maintain good communication within the project stakeholders: communicate with your pears, with your managers, with your vendors. Good communication within the team is the key to a successful project.

- Understand your tests: there is no way to emphasize it. In any process – manufacturing, alignment, calibration and control – you must understand the tests you make and their results, the test and measure equipment and its accuracy and the limitations of the gear you use. You may make assumptions in the beginning of a project when data is missing or unavailable but, when going into final manufacturing and assembly or final calibration process no assumptions can be made.

- Ensure clear assignment and responsibility: although it rhymes with good communication it deserves a point of its own. A big part of the misunderstanding that the primary mirror was malformed originated from the lack of a real responsible function from within NASA’s HST team.

- Do not forget urgent vs. important. We always have constraints and directives from the top brass however, when the risk for an out-of-spec product materializes these directives should be challenged (when possible – I know that arguing with an army general is usually impossible).

- Documentation – need I say more?

Once again, these lessons are relevant for any multidisciplinary project especially the large scale ones.

This is a good place to stop for this post.

In the next post we will cover the solution for this issue optics-wise and system-wise and how a daily shower in Europe paved the path for a solution to a very interesting engineering dilemma.